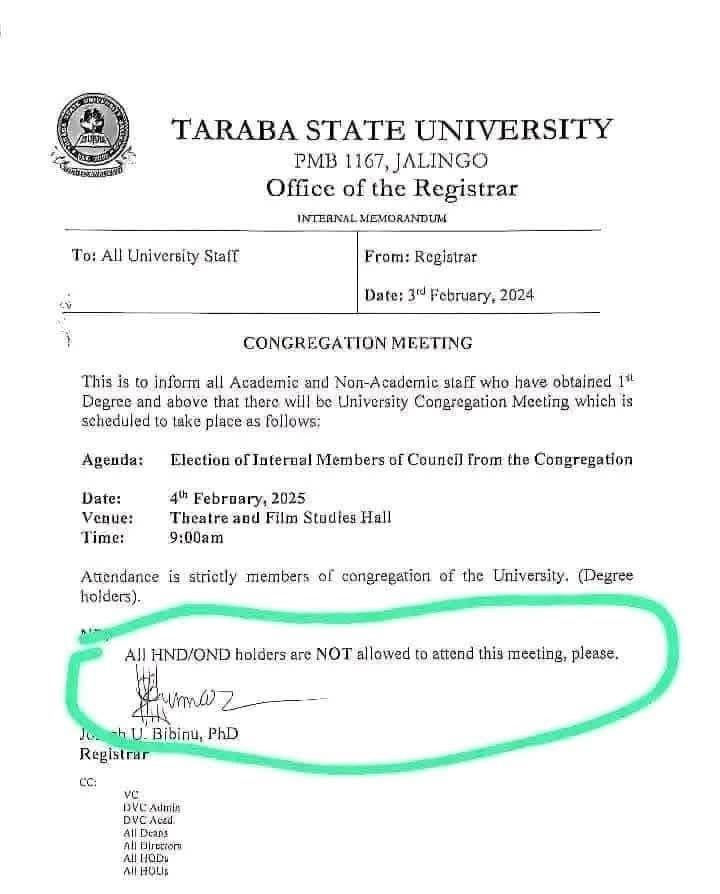

The HND/BSc dichotomy has long been a source of frustration and inequality in Nigeria’s education and employment sectors. While both qualifications require rigorous academic work and practical training, HND holders face systemic discrimination, particularly in government jobs and private sector placements. Many companies limit HND graduates to lower career levels, restricting their chances of promotion and professional growth.

This bias not only stifles individual potential but also hinders national human capital development, as thousands of skilled and capable professionals are sidelined due to an outdated classification system. In a world where technical and vocational expertise should be valued alongside traditional academic degrees, Nigeria continues to reinforce a class divide between polytechnic and university graduates, to the detriment of its workforce.

Beyond the employment barrier, the HND route is a significant waste of time for many students who choose it, often out of financial constraints or admission difficulties in universities. While a BSc degree typically takes four to five years to complete, HND graduates spend two years in ND, another two in HND, plus an extra year of mandatory industrial training (IT), totaling five years, yet they still face limitations.

Many are forced to undergo additional “conversion” programs to obtain a BSc equivalent before they can fully compete for jobs, resulting in prolonged academic years with no guaranteed career advantage. This inefficiency discourages technical education, leaving polytechnics struggling with declining enrollment as students opt for university programs to avoid discrimination.

For some fields, the HND qualification is practically terminal, making professional certification nearly impossible without additional academic upgrades. A glaring example is Architecture, where HND holders cannot obtain full professional licensing until they complete a university “conversion” to BSc Architecture before proceeding to an MSc or the necessary professional exams.

This puts HND graduates in a disadvantaged loop, forcing them to either spend extra years bridging the gap or abandon their career ambitions altogether. Such structural barriers devalue polytechnic education and create unnecessary obstacles for skilled individuals, limiting their contributions to national development.

The refusal to eliminate this outdated dichotomy not only wastes time, talent, and resources but also slows Nigeria’s progress in key industries that rely on technical expertise. The 2021 Bill, which aimed to abolish this discrimination, was a beacon of hope, yet it remains unsigned, leaving thousands of graduates in limbo.

Instead of directing anger at institutions like Taraba State University, who recently published employment opportunities exuded these previously highlighted biases, efforts should be channeled towards pressuring the National Assembly and the Presidency to revive the bill. HND holders, student bodies, and advocacy groups must intensify their push for reform, ensuring that every qualification is given the respect it deserves. Only then can Nigeria build a truly inclusive, fair, and productive workforce that maximizes the potential of all its graduates.

Idris Animasaun

Architect and Social Change Advocate